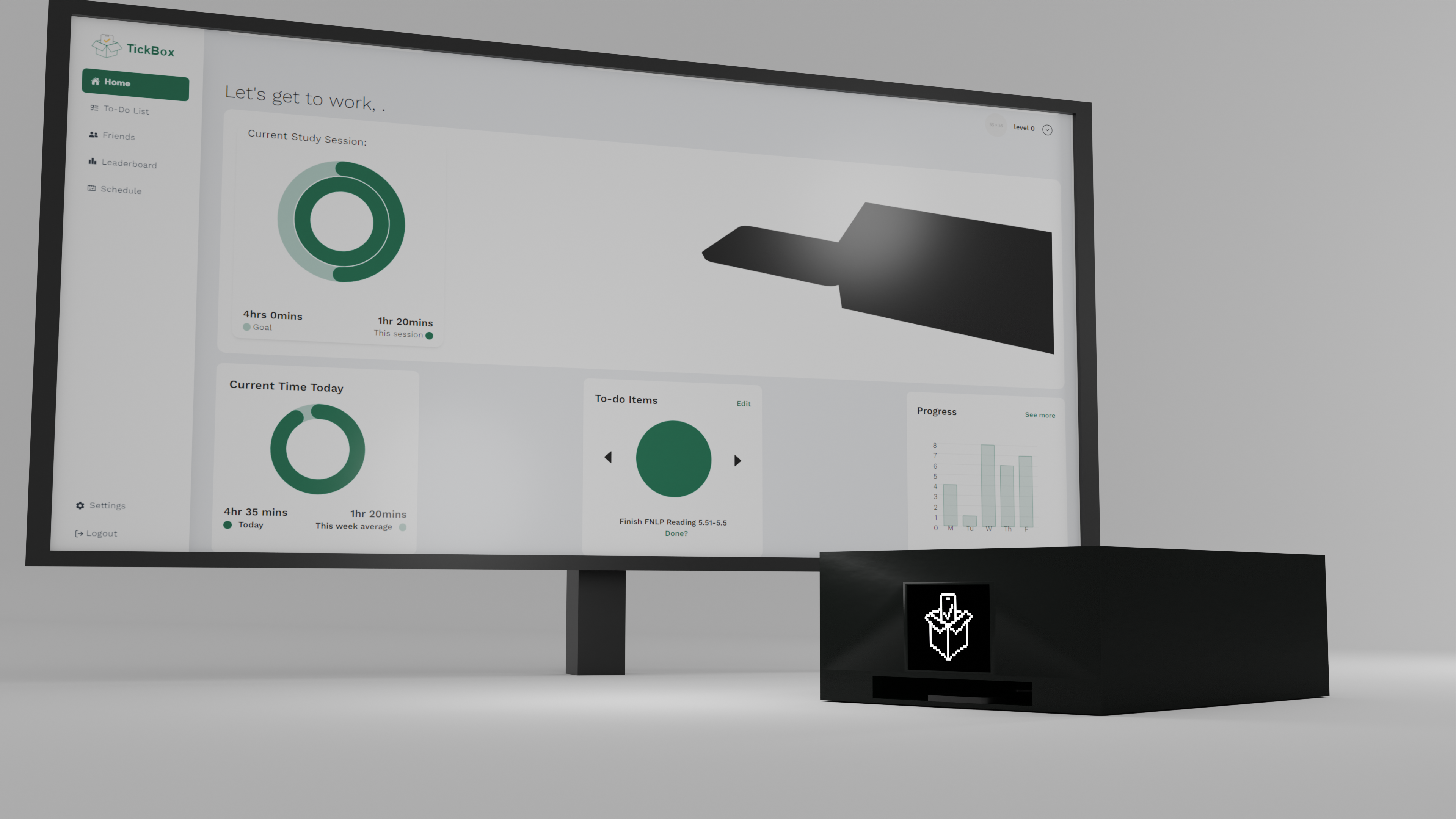

Tickbox

a hybrid web-based/robotic project aimed at keeping students off their phones

As part of the University of Edinburgh’s System Design Project course, our team had ~10 weeks to design, pitch, create, present, and critically reflect on a product born from the following prompt.

A robotic appliance that helps the human user in some capacity where they have difficulty to complete the task themselves

We created Tickbox, and this page details what we did, why we did it, and if we would have done it differently.

What was the problem we aimed to solve?

As the course started, we started to think of problems that people would face. We unfortunately started with a lot of ideas (and solutions) that had been covered in previous iterations of the course. Eventually, we realised the idea had been staring us in the face the entire time (at a downward angle, on a small screen) - phone addiction.

Once this idea was suggested, every member of the team was on board. Everyone agreed they would prefer to spend less time on their phone, but the addictive algorithms would keep them from finishing their coursework. We hypothesised that many people had difficulty with this task and confirmed this with our self-ran user studies. Our studies1 revealed this hypothesis to be worse than we originally thought. In particular:

- 89% of respondents said they commonly find themselves distracted by their phones while studying

- 52% of respondents considered their academic performance at University to have worsened since high school

The works of (Andrew Lepp, 2015) and (Sahu et al., 2019) also confirmed that we should get to work on a device that would help students finally get off that damn phone.

The idea of Tickbox

User Studies

We looked to other products aimed to solve this problem. A commonly used app used by students, including some members of our team, was Forest. This provides a solution using gamification, which we saw (through other apps such as Duolingo) can be an effective tool to get otherwise stubborn minds to be productive.

We wanted to do more than just an app, however. Our studies found that since 80% of users found they worked better with their phone out of sight, some form of hybrid robotic/software solution was needed. The concept of “phone lockboxes” already exists, with popular examples such as The Virtus Project already establishing their place in the market. Nevertheless, we tested the appeal of this idea by asking our potential audience, “Would you focus more with your phone in an opaque box than rather than just using a focus app?” Only 50% responded yes, with 40% responding maybe. Rather than take this as a setback, we understood the following from our results - 50% of users would probably be happy if we remade the Virtus, but we could win over that 40% by incorporating ideas from both solutions.

Designing Tickbox

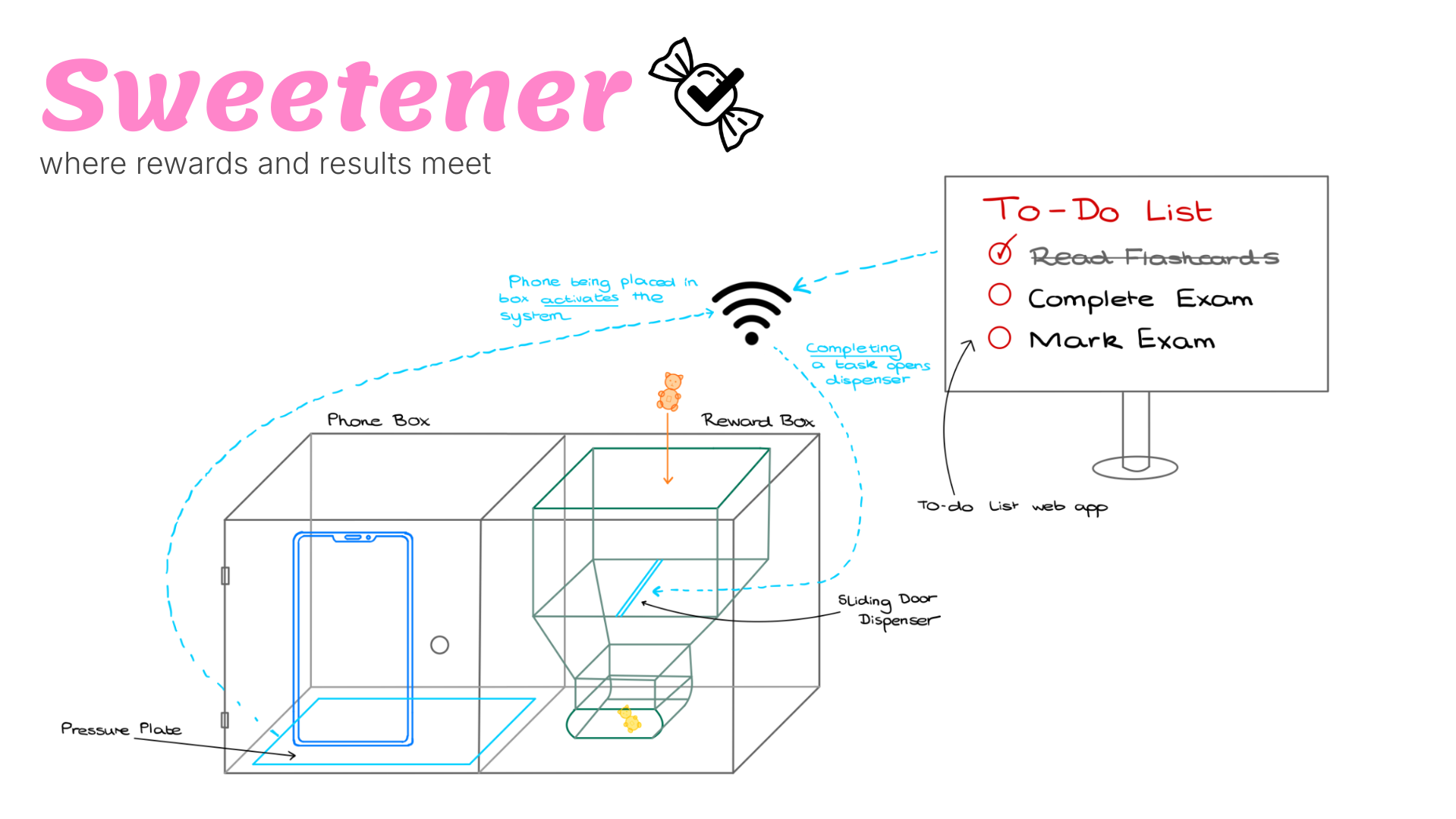

So, some form of phone lockbox with a gamified software component to go with it. At the end of the first week, we created the first quick proof of concept of what would become Tickbox.

While this design was iterated upon heavily during development, some key ideas of it stuck:

- A mechanism to detect whenever the phone is placed in the box

- A web-based frontend, acting as a to-do list linked with the box

- A reward dispensing mechanism, rewarding the user whenever they complete a task with their phone in the box

Initial Feedback

One piece of immediate feedback we received was the fact that while phones are a distraction, they’re often an important factor in our lives, especially when it comes to emergencies. While an AI voice reading AskReddit posts over Minecraft parkour footage is not a productive use of one’s phone while studying, responding to a doctor, parents, or significant others is something people said they’d still like to be notified about.

We also had some criticism relating to the bulkiness of the design. We immediately realised that, with single phone usage, we could scale back the phone chamber significantly. Additionally, we realised not all users would want the dispenser apparatus at all times, so we proceeded with the idea that the box could have modules. This added value to our product during pitches, since future versions could have extra, purchasable modules.2

The idea of having sweets dispensed got some pushback from the course organisers. They appreciated the idea of rewards linked to tasks, but worried that students may find themselves addicted to the sugar in the rewards. After trialling many ideas, we eventually decided that individual LEGO pieces - which allow users to create a “trophy” of their accomplishments - stuck with both our intended audience, and even our initial critics!

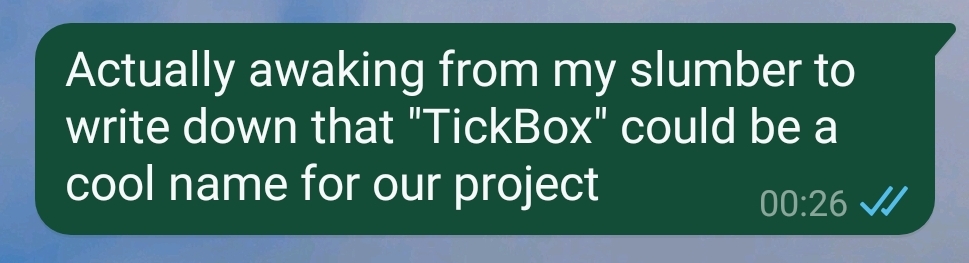

This change did require a chance in our branding. After our pivot away from sweets, a few days later I awoke in the middle of the night with a vision for our project and immediately told the team.

I can happily provide my expert-level midnight branding decisions to future projects if any potential employers are interested.

Creating Tickbox

The course was split into 3 “demos”, each highlighting how our project evolved based off feedback.

Demo 1

We were provided a Raspberry Pi to act as the microcontroller for the box, and my responsibility for this stage was effectively “figure out what we can and can’t do with this tech”.

I quickly spun up a few test programs to interact with the Grove I/O devices we were allowed access to. At this point, we had team allocations all sorted, so my teammates took over this field and I ventured into other avenues.

We knew our idea needed to mature and so I set out to improve the box itself. We had the idea that the box would have a small screen to display certain crucial features. The original incarnation was to just have the screen mirror the website to keep all our design in one place, but the screen we were provided was proprietary and poorly documented. While it allegedly had the capabilities to display a HDMI image, >5 hours of troubleshooting (until the University workshop closed for the evening and we had to leave) left us with the fallback tty option.

Life in the terminal is quite monochrome, and since our screen was about the size of 2 postage stamps put together, we realised we couldn’t just print text to this screen at this resolution. I decided to investigate the curses library provided by Python, and 2 hours later I had created a little program to turn a .mp4 video into a monochrome ASCII animation!3 To present in our demo, I settled for a more plausible timer; 4 seven-segment display-style numbers representing MM:SS. Since the first demo was all smoke and mirrors (as we were tasked with making a prototype, and only our ideas were graded at this stage), we suggested this as a “study timer” (think Pomodoro) the user could glance at - even as TickBox evolved, this idea made it into the final product.

We also added an NFC sensor to detect when the phone was in the box. Due to the short range and the small size of the phone chamber, it’s incredibly difficult (and we deemed impossible to the average user) to “trick” Tickbox into falsely believing you’ve put your phone away.

Demo 2

We had to end this demo period with a working product.

I quickly passed over my knowledge on how to use curses to my teammates and moved over onto what would become my main focus for the rest of TickBox - the backend.

One of our original suggestions for TickBox was that users didn’t need to use our proposed tasktracker, and we could develop extensions for commonly used note-taking apps to integrate with TickBox. I was tasked to create the API to bridge the gap between our frontend and the box itself.

Having made enough CRUD databases to do it with my eyes closed, I quickly whipped up a Flask application with sensible endpoints. I then set about cloning the frontend repo, and making sure it could communicate with the backend and update

Maybe my apt had a dodgy update. Maybe I’d typo’d a package I hadn’t installed. Maybe node.js just decided to take the day off that day - I could not get the local server to start. I did need to work on this integration with the backend, so I decided to use one of the features present in my GitHub student account - codespaces.

A codespace is a Docker-powered devcontainer hosted by GitHub. Regardless of it’s many benefits, the main draw to me was that I could get the frontend working here! As I was working, it dawned on me: this was a cloud hosted platform I was developing on. A cloud hosted platform. What would happen if I started up the “local” server?4 To my surprise, the URL to my codespace was appended with a port number and live-hosted on the world wide web! I could even access this website on my phone, which for some reason made the project feel even more real than seeing it on a laptop screen.

“But wait…” I thought, “what if I could host the backend on a codespace at the same time? Would they be allowed to communicate?” I fiddled with some endpoints and BINGO! I had two hosted apps confidently talking to each other! The final stage here was to get the box itself talking to the API. The backend effectively acted as a “bridge” between the box and the frontend, storing user data and informing each of the other listeners what the user was doing. We went with WebSockets for this communication, and after many teething errors5 we completed our tasks on the frontend, saw the backend update, and the motor on our box released a reward. To us - tired and worn down at 6pm - this must’ve been how the scientists at NASA felt when they first successfully landed on the moon.

Demo 3

We had a deadline to fully finish the project. I worked ever closely with the front-end and hardware (box) team to add more features to our product. To ensure reliability, I created a thorough unit testing suite using Postman to ensure the core functionality of the backend worked as features got added.

We added a friends system and leaderboards to the webapp to encourage friendly competition. Many of our users indicated they liked studying with their friends to hold them accountable, so adding these gamified features would help even in solo focus periods. The hardware team also cooked up an excellent notification detector and I helped incorporate a custom list of words into a user’s settings to filter their most important notifications. Our final Tickbox addition was a feature conceived close to inception - the “Tickagotchi”. This was mainly the idea that by being productive, you’d be taking care of a small cute pet. This manifested in an optional toggle for a study session, where a user failing to complete their tasks and taking their phone out would “upset” the Tickagotchi.6 The hardware team designed a few faces for the Tickagotchi to change between.

My last few tasks before the final presentation were optimising the backend, stresstesting it with Postman, and fixing bugs with all parts of TickBox and all members of the team.

What worked, and what didn’t

Codespaces should never ever be used for hosting purposes and in retrospect I don’t know what we were thinking

I’d argue that Codespaces are excellent tools if you just need to quickly test a CLI app and don’t fancy setting up everything locally, especially if you don’t have good access to devcontainers. However, since they are primarily a programming platform, they are not suited to long-term hosting. Each person’s codespace is assigned a random identifier, and has a (by default) 30 minute inactivity timer before shutting down. This meant not only did our confusing endpoint need to be hardcoded, but that person would need to be active for all development time. Any member could spin up a backend codespace if they wanted to personally test something, but was required to manually enter the long URL into the Pi. This overall process was quite ridiculous in retrospect; we really should’ve forked over the money for a proper, dedicated host. It did stand up to the stress tests mind you, which GitHub likely wasn’t a fan of.

Network woes

Our course gracefully provided us with many materials, and even had a dedicated network for machines in the lab to talk to each other. The problem? Machines on this network were not connected to the wider internet. This makes it troublesome to install packages locally onto the Pi, or simply connect to a remote repository on GitHub! We eventually found two ways around this: we found a way to connect onto the more general eduroam (allowing for exterior connections but not internal ssh), and sshing via the lab computers, which we could also use external connections from. We did have a brief period where these solutions were not apparent to us, leading to… “unorthadox”, less efficient methods of getting code onto the Pi.7

2 people per task, minimum

I generally consider our teamwork and planning quite admirable with one major oversight. Physical production of the actual box was left solely to one person as they were the only one who possessed serious CAD skills out of our group. Unfortunately, this team member had numerous other commitments during the semester and, as a result, we only had our first physical cut box in week 9 - of 10. This meant we basically had to settle with what we had, as further iterations were out of our time limit.

Modules? What modules?

While we did originally intend to develop multiple modules, we only developed one - the dispenser. To remedy this, TickBox was developed with both the software and hardware flexbility to support swappable/multiple modules (via detachable cables and generic reward signals in the API). We did check that modules could’ve been swapped out, but this was with rudimentary small bundles of cables and LEDs, and not any actual dispenser to be promoted.

The TickBox API

Speaking of the API, I was very happy with the end product. During the Demo 3 sprint we found it incredibly easy to materialise our ideas within the hour they were suggested in. Testing infrastructure was organised and re-usable; I didn’t have to write any new tests per-say for our stress testing, I just automated a few of our existing unit tests en masse.

The Achilles Heel of the NFC

Our NFC sensor worked incredibly well. No matter what phone was put into the box, it was always picked up incredibly accurately. We could also detect the NFC ID of the phone, meaning this could be used to log in. Unfortunately, we prioritised other features of Tickbox, and this feature was left as something to sell our “future product”.

The main problem with NFC rested solely on Apple. We found that Android phones would happily share NFC at any time, but Apple phones would only want to give off an NFC signal when Apple Pay was active. The fact that Apple users had to open their credit card to use our device was an annoying compromise, and the subject of many in-jokes within our team.

People really liked the Tickagotchi

For a last minute addition, the Tickagotchi stole the show when we presented our penultimate demos. It acted as a replacement for the dispenser module, although since it was entirely software we distanced ourselves from calling it a “swappable dispenser”.

People really liked everything else about Tickbox, actually

After Demo 3, we then presented our ideas to a small group of industry professionals. We were worried going in, but the presentation went off without a hitch! Some of the older members found it difficult to relate the notably young problem of phone addiction, but other members were immediately sold that they requested to “try their phone” in the box and operate it for themselves!

What did we learn from Tickbox?

TickBox was a beneficial learning experience to us all. We learned the reaches of ambition, and how to deal with reality when it compromises our dreams. We learned the benefits of smart, fluid team allocation, and regular communication. We learned numerous technologies, and became proficient setting up Flask servers and managing websockets. We learned how to professionally present ideas, progress, and products.

Most importantly, we learned that the greatest factor towards an excellent team product, is an excellent team. I am incredibly thankful to have worked with such a hardworking, devoted, communicative, welcoming, and tightworking team, and I am incredibly proud to have worked with everyone on such an amazing product.

Footnotes

-

Study conducted by SDP Group 1 on 60 respondents from the University of Edinburgh in January 2024, approved by the University’s Ethics Board to not contain any identifying data. ↩

-

Some ideas we came up with were a flashcard “carousel”, a catapult, a real world leaderboard (to see how your friends were doing), and a Tickagotchi, who you’d have to keep happy by staying off your phone and being productive. Remember that last one, it’ll come back later. ↩

-

This video playback functionality ended up unused in the final product, as it stood as more of a “proof of concept” of what we could achieve with

curses. ↩ -

If you’re reading through this wincing a little, this will be addressed further on. I’m taking you on the journey of TickBox as we experienced it. ↩

-

Did you know the Python

socketiopackage absolutely does not work anymore, and everyone should absolutely use thepython-socketioinstead? It took the entire team about 8-10 combined frantic debugging hours (assuming we were making an error on our end) until we found a comment mentioning they switched to this 5 pages deep in a GitHub discussion so esoteric I can’t even find it anymore. Thank you to that random person, we almost pivoted the project hard. ↩ -

We did not allow the Tickagotchi perish or fall into harm in any way. A sad expression was enough encouragement. ↩

-

Some personal favourites were plugging a keyboard into the pi and navigating the cli via the tiny screen and manually coding in

vim, and the strategy of getting a USB stick, plugging it into another computer, copying the file onto that, unplugging and replugging into the pi, andcp‘ing to the core filesystem. The second option felt dirty to do even at the time. ↩

References

2019

- Mobile phone addiction among children and adolescents: a systematic reviewJournal of Addictions Nursing, 2019

2015

- The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College StudentsSage Journals, 2015