Dockerising everything

In the summer of 2024, I made a change.

I’d naively brought my gaming PC to uni so I could continue my teenage hobby in my downtime. But SURPRISE! I instead spent my free time engaging with new friends and societies, working, and discovering more about my degree. All my computational needs were more than covered by my laptop, and the desktops the university supplied. It wasn’t uncommon for my keyboard to sit collecting dust.

The problem was, even if I wanted to play today’s games, my PC was (by today’s standards) “pretty low end” (Battaglia, 2024). However, years of bloated program installs meant it wasn’t a fun experience to try and do programming for uni on it either.

So mid-summer, I wiped the drive, and installed Debian.

I’d been looking at Linux distros for a while, and the one that really grabbed my attention was NixOS, mainly for the feature that you could get an identical setup on two different computers, all managed by a single file. It did seem like it came with some caveats1 so I decided on good old fashioned Debian to match my Ubuntu’d laptop. The question then became, what was the best way to have the same development environments when using two different machines?

What is Docker?

The following is not a comprehensive (or even fully correct) explanation of Docker. It’s both a primer for how I use it, and the explanation I wish I had found when trying to work out what it was.

A virtual machine is a program that simulates all the physical parts of a computer in code, to the extent that you can load an operating system into it and run it inside of the program. In theory, this is a great idea for developer environments - load up a VM, install what you need inside there, and then reopen it every single time you want to code using the tools! You could even have multiple VMs for different coding environments!

The downside to this is VMs are designed to load the entire operating system, which means you’ll be simulating all the memory management, background tasks, fancy desktop effects, file management, etc even if all you want to do is make a simple calculator in Rust.

A container is effectively a very lightweight VM. It’s usually designed with one purpose in mind - imagine a VM, but with every unnecessary bit hacked off. Docker is just a program that acts akin to a virtual machine manager, but for these containers. It is needed for these containers to run on your computer.

That’s not all Docker does - I haven’t even touched on images, which are basically templates for a container and allow Docker to run more efficiently - but this was enough for me to realise that by installing Docker, I had my solution.

How did I use Docker?

Confession: I used devcontainers.

Devcontainers (once again, to me) are basically a wrapper for containers, but their main advantage was the fact they integrated incredibly well with VSCode. Docker can sometimes be a bit tricky to get the stuff you want inside of a container, but here the process was as simple as clicking Reopen in Container and waiting for my environment to be built.

I would simply create a base devcontainer.json file inside of each of my repositories, and slowly build up my desired environment through changes to that file (corresponding to commands and options). This meant, as long as I had VSCode and Docker installed on a machine, I could have the exact same experience. This also let me leverage GitHub Codespaces, which already use devcontainers to set everything up. If I really wanted to, I could even open the codespace in a web browser.

What were the results?

Initially, everything was coming up Milhouse. I made devcontainers for each of my courses, aswell as a \(\LaTeX\) writing one, and a few more.

The problems began once I tried to replicate these on my PC.

Firstly, you may have noticed that if I’m ultimately still using a VM (via a container), then all my files are on that VM, right? Docker provides a system called a bind mount, which takes your current repository, and mounts it as the filesystem to the container. This means, if your container writes something to this filesystem, it actually appears on your real filesystem! This keeps containers small, and means you only need to commit the files you want to change.

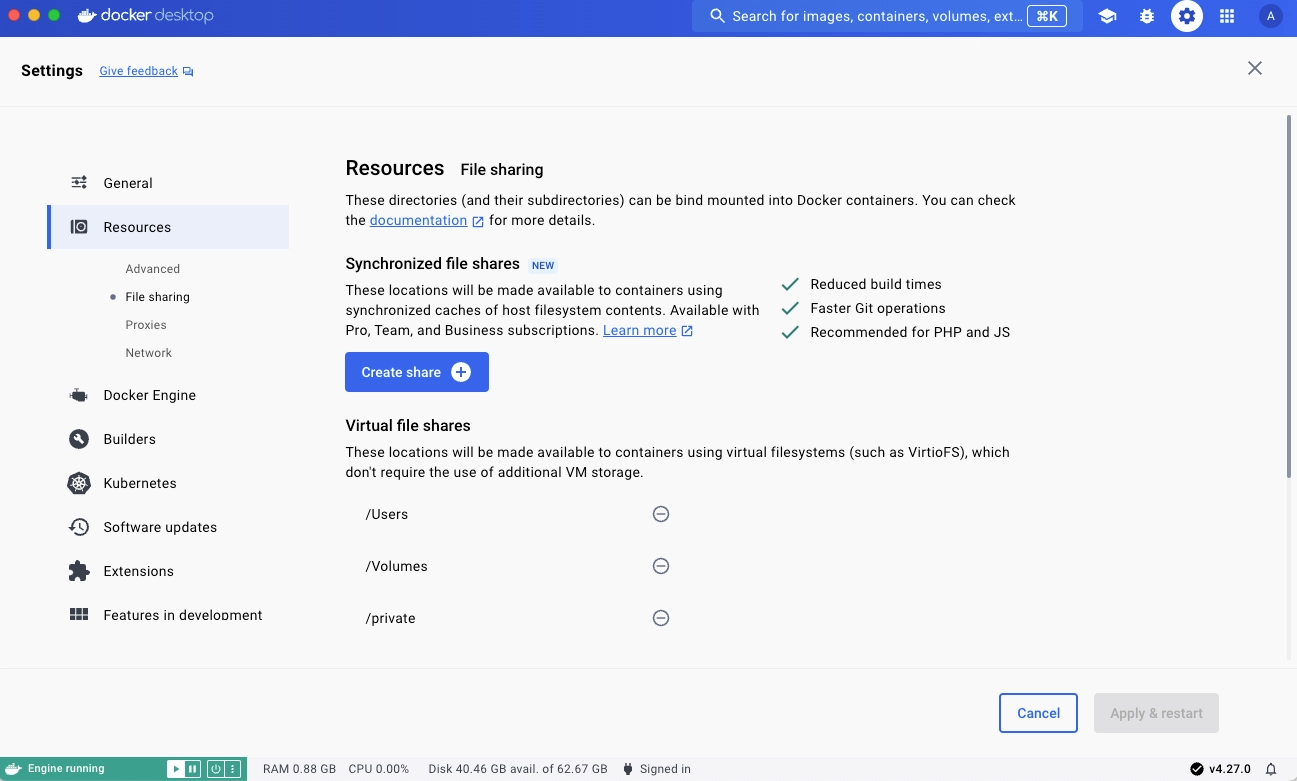

That being said, my containers failed to build on my PC, and after a few hours of bug hunting, I found the problem: Docker only (initially) allows you to mount folders from your \home directory. I was hosting all my desired repositories on a separate drive. The only solution I was able to find was to add these volumes in Docker Desktop.

This irked me, as Docker Desktop is effectively completely uneccessary on Linux, and while this fixed my issue, it caused even more relating to specific system-wide docker configurations I had made to get my idea working.

Mainly, this related to trying to pass-through my GPU to containers in anticipation of heavy machine learning tasks. This requires installing a specific NVIDIA “container runtime”, and plain-and-simple does not work if Docker Desktop is installed. So given the choice between not having GPU’s passed through to containers and not having them work at all, I chose the former.

Then there was the issue that sometimes containers just failed to build on certain systems. I could not get my Agda container to build on my laptop, despite working perfectly fine in codespaces and even on my problematic main PC. The only solution to allowing my \(\LaTeX\) container to access git repositories in it’s fileshare was the hilariously insecure chown root:root .

Finally, containers are a jack of all trades, but I just didn’t find myself needing them. It would’ve been nice to open up a container hyper-optimised for every task, but most of my courses just required a Python virtual environment, and those which didn’t were better suited to not using VSCode at all. As for that \(\LaTeX\) container, I found it just easier to use Overleaf.

Epilogue

I’m glad I finally learned Docker this summer. I can see how the tool is incredibly useful, and understand why many home server setups adore running isolated containers. For me, it was like taking a chainsaw to a toastie: it’ll do the job, but you might crack your plate and you’ll probably get ham and cheese all over the walls.

-

The ones I recall were: NixOS stores programs in unusual paths which causes issues with some dependencies, I wasn’t sure how long boot times would be considering the OS would “rebuild” itself often, I was worried I’d version stuff incorrectly, I’m still unsure what flakes actually are, and I may spend too much time editing the config instead of actually doing work. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: